Monty on: Austerity's Silver Lining

5 min read

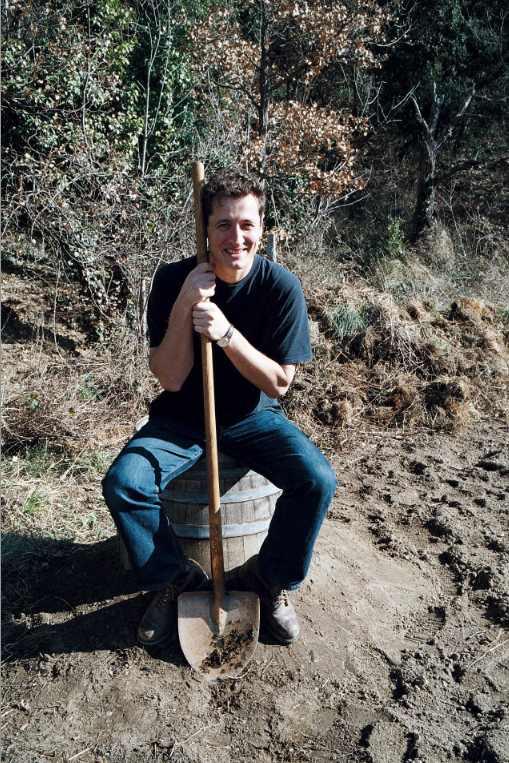

by Monty Waldin

Not everyone likes this new age of austerity. But from my perspective as a lover of both biodynamic wine and gardening I think a little bit of austerity may not be such a bad thing.

Brits import 70% of their groceries rather than grow their own, and buy 70% of that imported 70% from supermarkets and convenience stores.

As the credit crunch started to bite fuel costs skyrocketed due to huge demand from China, and instability in both Libya and Iran.

As the oil price rose, so did food prices for UK shoppers so reliant on airfreighted or trucked in tucker. Food prices rose also because most of the “convenience” food we eat is grown using soluble fertilizers, weedkillers and pesticides, all of which are derived directly or indirectly from those increasingly expensive petrochemicals. Higher prices due to poor (global warming-affected) grain and rice harvests also played their part.

The happy result is that more people are home gardening. In the 1970s, people (like my parents) home gardened partly because it was part of a post-hippy zeitgeist (a BBC TV comedy drama called The Good Life about home gardening became a smash hit) but mainly because home gardening saved money in an era when Britain’s faltering, three-day week economy was known as “the sick man of Europe”. Growing your own means having much more autonomy over what you eat and what price you pay.

During World War Two people grew their own too, to “Dig for Britain” because “there’s a war on, you know…” as the saying went. Although times are tough now for very different reasons the result is self-sufficiency, which is seen as A Good Thing and not something to be embarrassed about.

An hour a day of gardening keeps you fitter than several hours of jogging, whilst giving you better quality, fresher, seasonal food. It saves you money too – supermarkets make profits on even their “cheapest” food lines by screwing farmers. Growing your own also keeps you mentally fitter too. You are more in tune with the land (even if it is only your tiny suburban patch of it), the weather and even, dare I say, lunar cycles. Sales of lunar calendars like Maria and Mathias Thun’s Sowing and Planting Calendar are absolutely booming, and not just amongst those who like me feel that there is some sense in hoeing, sowing and harvesting your carrots and cabbages under the “right” moon.

I got into home gardening as a small kid, long before I got into wine. My earliest memories are of making compost from leaf mould and cow manure with my dad for our vegetable garden. He grew up during the last great age of economic austerity, the 1930s Great Depression. He’d collect manure from the horses pulling the milk dray and use it for his blind, war-wounded (Ypres, 1917) father’s tomatoes.

I loved the idea of recycling what others saw as waste (fallen leaves, fallen manure) to grow healthy food. So when I got into wine I gravitated to wines made naturally, meaning wine from vines grown using worm-rich composts rather than wine grown using sacks of factory-made fertilizers. I’ve never once seen a worm in a sack of fertilizer and I’ve opened trailer-loads of sacks of fertilizer.

I worked on an organic vineyard and liked it, or at least preferred it to the “chemical” vineyards I had also worked in. But I felt organics did not go far enough. A link was missing. I finally found this missing link when I discovered biodynamics. I felt biodynamics was a natural fit for me.

Biodynamics places self-sufficiency at its heart. Organics also does this but not quite to the same extent. In organics what seems to matter is avoiding “chemical” fertilizers. Organics is as much as about what you “cannot” do as what you should be doing. This is why organics does not force farmers to grow what they need for “organic” compost.

In biodynamics on the other hand what matters is fertilizing your soils with piles of compost you made from what you have recycled from your own farm/vineyard. And the best compost is made using animal manure, especially from cows whose manure is pure gold if you want the healthiest crops and soils (as any Indian farmer can tell you). Hence biodynamic vineyards can’t just have vines and nothing else, they must get some livestock onto the land too: horses to plough soils, chickens and sheep to graze weeds and bugs in winter, plus cows for their meat, milk and – most important of all – their manure.

The most successful vineyards on the planet right now have their own cows. How do I define success? First, wine quality. You can’t make good wine from soils which are unhealthy because they have been sterilised by weedkillers and artificial fertilizers. Second, vine quality. If your soils are richly fed with worms and the good microbes compost contains then your vines and their grapes will possess an in-built resistance to pests and diseases.

There is a growing and I believe unstoppable trend for the world’s greenest vineyards to spray their vines only with 100% natural and locally harvested materials: teas made from wild plants and herbs growing in or around the vineyard (yarrow, chamomile, stinging nettle, oak bark, valerian, thyme, rosemary, garlic, fennel, seaweed and so on) or teas made by soaking then stirring a few handfuls of mature compost in water. Such teas and composts keep vines and soils well fed whilst protecting them with a coat of living organisms that keep the bad bugs out. This way of farming means the need to pick up the ‘phone to order costly industrial sprays made unsustainably and shipped from unsustainably far-flung factories is nullified. No wonder agri-business detests biodynamics with a vengeance. In biodynamics you learn to make everying you need on the farm. So you end up putting more into your farm than you take out. This is truly sustainable.

The other thing I like about biodynamics is that whereas organics is rightly concerned with soil health – what is beneath your feet – biodynamics also goes a step further by then making farmers think about what is going on above their heads, meaning lunar and other celestial cycles. Biodynamic farmers think that plants grow the way they do partly because of what substances they get to eat from the soil (nutrients) and atmosphere (photosynthesis) but also because of forces exerted on plants by celestial bodies like the sun and the other stars, and the moon and the other planets.

We’ve lost our connection to nature and natural cycles (like the four seasons) because we can buy fresh strawberries 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. Biodynamics helps us re-make that connection and is why biodynamic farmers define good food as being food which provides all the physical stuff we need to grow our bodies (nutrients, proteins, vitamins) plus the right forces we need to grow the bits of us that make us sentient, thinking beings. What separates us from animals is we know we are going to die, the “I think therefore I am” idea.

The dilemma unique to us as we face our own mortality is do we leave something (our planet) for our kids to enjoy or endure?

Biodynamics gives us a tool to deal with that dilemma by producing food and wine which doesn’t cost a tonne of petrodollars – or the earth – to produce. Food which is good for both body and spirit. We should all drink to that.

Monty Waldin has been writing about biodynamic wine since 1995. His latest book, Monty Waldin’s Biodynamic Wine-Growing will be published in June 2012 (lulu.com).

Monty and permaculturist Mark Garrett are hosting a green gardening Q&A at RAW WINE on Sunday 20th May at 1:30. So pop along with your questions and meet them both in person!